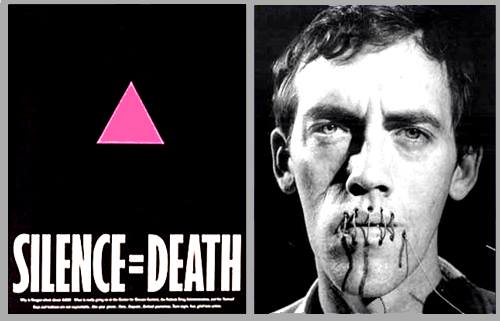

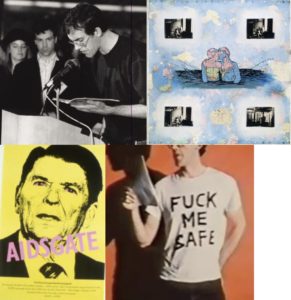

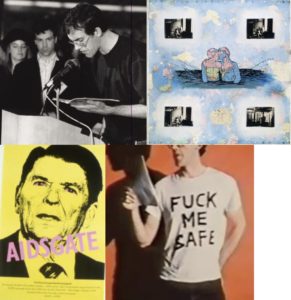

Clockwise from top right: David Wojnarowicz, Fuck You Faggot Fucker, 1984; “AIDS Trilogie: Silence = Death, 1989 film” by Rosa von Praunheim with Phil Zwickler; Granfury, AIDSgate, 1987. Retrieved from Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library; David Wojnarowicz at “In Memoriam: A Gathering of Hope, A Day Without Art,” MoMA, November 30, 1989. Photo by Star Black © Star Black. Department of Public Information Records, II.B.2406. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

“David spoke to the universe,” explains Anita Vitale, board chair of The David Wojnarowicz Foundation. “His voice could move you, that deep voice. He could capture an audience in the palm of his hand. He was amazing that way, and his eloquence, and speaking on all levels and to all people.”

Philip Yenawine, once Director of Education at The Museum of Modern Art, remembers David as “… the most cogent, useful, arresting, challenging voice in the activist world… [David] was omnipresent.”

Hugh Ryan, non-fiction writer and historian of queer politics, culture, and history, sees David as an activist provocateur. Ryan suggests David may have even created one of the first memes when modifying his blue jean jacket to read: “If I die of AIDS, forget burial and drop my body on the steps of the FDA.”

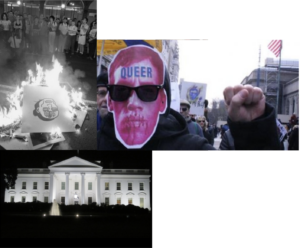

Clockwise from top right: Gun Safety demonstration poster, March 2018 from ACT UP New York Instagram; Gran Fury (Artists Collective), You’ve Got Blood on Your Hands, Ed Koch (Poster on the base of a traffic light), 1988, The New York Public Library Digital Collections; David Wojnarowicz at ACT UP FDA demonstration, Rockville, Maryland, October 11, 1988. Photo by Bill Dobbs courtesy of The David Wojnarowicz Papers at The Downtown Collection of Fales Library & Special Collections at New York University.

New York-based writer Lauren O’Neill-Butler explains the text of David’s bespoke jacket “has turned into its own image “virus” and has mutated, as variations on a meme. Adopted by different people in different cataclysmic circumstances, the transmuted text in each case has condemned a government that didn’t operate under conditions of maximum public transparency, nor communicate the real scope of a threat to endangered populations, nor implement measures of mass testing and preventive care. In the face of a public health emergency and a rising death toll, the people circulated their own infection.” Today a new generation has taken up these words of protest in support of gun safety and trans rights.

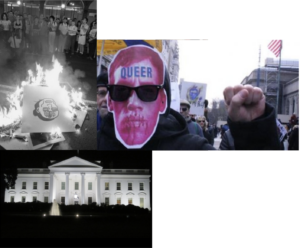

Memorial procession for David Wojnarowicz July 29, 1992. Photo copyright and courtesy Brian Palmer/www.brianpalmer.photos; Demonstration at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, against removal of a David Wojnarowicz video from an exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C., December 19, 2010. Image copyright and courtesy Theodore Kerr.

In the years after David’s death of AIDS in 1992, activists were inspired to take three daring actions in David’s name.

Friends and activists held a memorial procession throughout the East Village complete with bonfire in response to David’s call to respond to AIDS deaths with “a relatively simple ritual of life such as screaming in the streets…”

David’s partner, Tom Rauffenbart, joined ACT UP’s second Ashes Action to scatter David’s ashes on the White House lawn inspired by David’s memoir Close the Knives: “what it would be like if, each time a lover, friend or stranger died of this disease, their friends, lovers or neighbors would take the dead body and drive with it in a car a hundred miles an hour to Washington DC and blast through the gates of the White House and come to a screeching halt before the entrance and dump their lifeless form on the front steps.”

Years later, demonstrators holding masks of both Arthur Rimbaud and David (with lips stitched shut) protested en masse after the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. removed his unfinished film, “A Fire in My Belly,” from the exhibition “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture.”

In defense of the film, critic Holland Cotter wrote: “That A Fire in My Belly is about spirituality, and about AIDS, is beyond doubt. To those caught up in the crisis, the worst years of the epidemic were like an extended Day of the Dead, a time of skulls and candles, corruption with promise of resurrection. Wojnarowicz was profoundly angry at a government that barely acknowledged the epidemic and at political forces that he believed used AIDS, and the art created in response, to demonize homosexuals.”

Lauren O’Neill-Butler notes, “[David] was known for his deep sense of parrhesia: an obligation to speak out, even at personal risk. The Ancient Greek tragedian Euripides, who coined the term, would have loved [his] capacity for refusing silencing and the production of false histories.”

Video: clip from AIDS Trilogie: Silence=Death, 1989, von Praunheim with Phil Zwickler